לכבוד יום העצמאות (ובגלל ששחכתי לשמור על קבצי הroot שלי כשעידכנתי ל-fedora 38), הגיע הזמן סוף סוף לפרסם את המקלדת המוזר, הארגונומי, והבהחלט יקה שבה אני מקליד בעברית כבר למעלה מעשור.

בגיל 16\18, נכנסתי לתקופת ניסיון. ׳תיודע, מסיבות טבע, פילוסופיה מזרחית, תוכנה חופשית ומקלדות ארטרנתיביות. כמו כולם 🤷. אז התאמנתי על דבוראק לכחודש ובסוף קבלתי הרגשות חזקות שהפחתי להיות איזה האקר קסום ואלוף. 5\5 מאוד מומלץ. כשעליתי ארצה בשנות האפסים התחלתי קצת ללמוד המקלדה העברי, וכמו כל המתחילים בזה, ההרגשה הייתה נגיד - פחות מדהים. אז פתחתי את הלפטופ והתחלתי ubuntu, פתחתי את firefox וחפשתי "hebrew dvorak keyboard layout" או משהו כזה, וווו-הופ! יצא תוצאה למקלדת שעיצב אהרון שלמה עדעלמן.

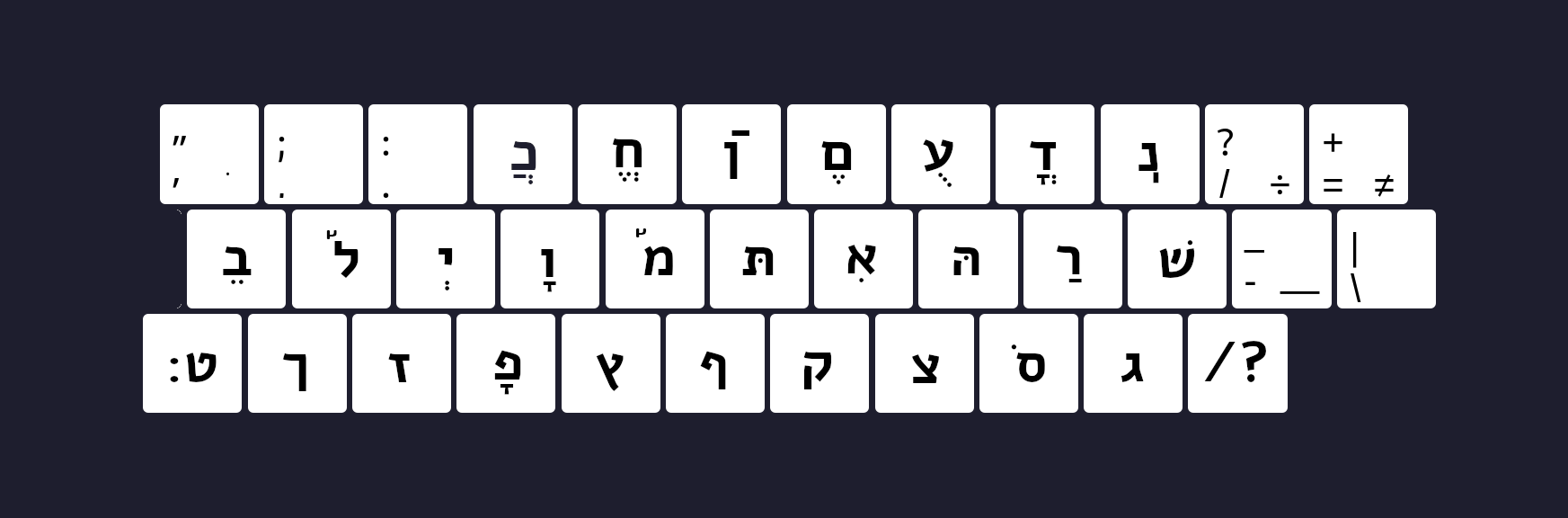

המקלדת מבוססת על דבוראק, כך שהאותיות הכי נפוצות נמצאות בשורת הבית. וגם הניקוד קל לגשת עליו כי הם פשות בשכבת ה-shift. הולך להקליד תיקון קוראים שלם? יש לך בשכבת ה-alt.

באו נקרא מה שהאהיש עצמו כתב על היוזמה:

Aaron has no information on the origins of the standard Israeli keyboard, but it certainly wasn’t designed for comfort or efficiency—it literally gave him carpal tunnel syndrome when he typed in 300 pages of Hebrew text one summer. Only 37.29% of all letters typed are typed on the home row, 34.74% on the row above the top row (which is a bit harder to type than the home row), and a full 27.97% on the bottom row (which is even harder to type). Furthermore, the left pinkie, a very weak finger, types 6.39% of all letter keystrokes, while the stronger left ring finger types only 3.90% of all letter keystrokes.

In order to overcome the problems with the standard Israeli keyboard, Aaron decided to create one based on the same principles of the Dvorak (English) layout. As far as he can tell, there is no other proposed Hebrew/Aramaic layout like this. There certainly is no Israeli standard layout based on the same principles as the Dvorak keyboard. Aaron’s keyboard layout puts the ten commonest letters on the home row (as opposed to a mere three on the standard Israeli keyboard), resulting in 69.50% of all letter keystrokes being typed there, only 19.66% on the top row, and 10.84% on the dreaded bottom row. This should result in less overall movement and thus less wear and tear on the fingers.

Furthermore, among the 30 commonest digraphs (sequences of two letters) in the first volume of the קיצור שולחן ערוך (an abbreviated code of Jewish law), 22 have the both letters on opposite sides of the keyboard (very ideal), 5 are typed on the same side of the keyboard but with different fingers (not ideal, but OK), and only 2 are typed by the same finger. For the same list of digraphs on the Israeli standard keyboard, 13 are typed with each letter on opposite sides of the keyboard, 5 are typed by different fingers of the same hand, and 8 are typed by the same finger of the same hand--and unlike my keyboard, some of this last category are typed with one letter on the top row and one finger on the bottom row, the most difficult possible combination to type.

Aaron has endeavored to make it possible to type every Hebrew character present in Unicode. Furthermore, under shift-option on the home row (showing up as blanks on the screen capture), are the very useful bidirectional formatting codes. From right to left they are: left-to-right embedding, right-to-left embedding, pop directional formatting, left-to-right override, and right-to-left override.

Aaron is not sure at this point he put the letters in all the right places. He has made sure to make the strongest fingers type the most keystrokes, and to make the right and left hands type about the same amount of keystrokes. But he is not clear he did everything right with placing all the keys in all the right places on their respective rows. Anyone with software for keyboard optimization, please contact Aaron to help him improve his keyboard.

Also note this layout is not designed for Yiddish, Ladino, or any other language which uses the Hebrew/Assyrian script, though no problem is anticipated for Aramaic; variations on the Adelman layout may be appropriate for these.

אז ככה, קבצי xkb שמאפשרים שימוש בlinux מוכנים ב-github ביחד עם קובץ ל-macos. תהנו ועצמאות שמח